- Home

- Stephen Madden

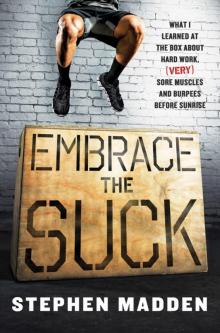

Embrace the Suck

Embrace the Suck Read online

{Courtesy of Mickey Brueckner}

Dedication

For my mother, Winifred Elizabeth Shannon Madden, who always knew I could.

Epigraph

We choose to go to the moon in this decade and do the other things, not because they are easy, but because they are hard.

—John F. Kennedy, September 12, 1962

Contents

Dedication

Epigraph

Introduction

1 The WOD

2 How and Why It Works

3 That Fleeting Feeling

4 Finding a Box

5 A Few Words About Pain, Fatigue, and Nausea

6 Diet and Body Image

7 The 20X

8 Nine Days in May

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Credits

Copyright

About the Publisher

Introduction

On a warm, overcast Saturday morning in July 2012, I stood, shirtless and barefoot, in the deep, dry sand of the beach in Avon, New Jersey, a 25-pound Tyvek bag of sand draped across my shoulders and neck in the same manner some other beachgoers that day carried plush towels. I was among two hundred people, most of them half my age, overwhelmingly male, astonishingly fit, breathtakingly tattooed—many with “Semper Fi” and “FTW,” a veteran’s mark of honor. Their mere presence made me self-conscious of the gray tufts of hair on my chest and the spare tire of fat around my waist. That the spare now resembled more of a bicycle tire and less of the tractor tire it had a few years ago was beside the point. Just a couple of hours earlier, safe in my suburban home, I had caught a glimpse of myself in a mirror and thought, “Hey, hotshot. Not looking too bad for a forty-eight-year-old. All those early morning workouts are paying off. Gonna look great at the pool club this afternoon.” It was one of the first times in my life that I looked in the mirror and truly liked the body I saw. But now, among the hyperfit, I was reduced once again to being the fat kid on the playground, a twelve-year-old who wants desperately to play but has trouble getting in the game. And when he does, is just not that good.

I was about to dive into the deep end of the sport of fitness as a participant in the second annual Warrior Challenge, a competition designed to test the overall fitness of its contestants with feats of endurance, strength, and speed.

And I was about to get my ass kicked.

After the presentation of the colors and the singing of the national anthem, an air horn blared and the first event, the sandbag carry, was off. We set off down the beach along a row of orange barrels that stretched for a quarter of a mile. We went at various paces, some at what sure looked to me like a dead sprint, some at a trot, me at a jog. That jog would last for four hundred yards, to the turnaround point, where my ragged breath and aching legs suggested I take it down a notch, to a brisk walk. That lasted another two hundred yards, until the walk became much less brisk. On the other side of the row of barrels, the leaders were running the second of their two laps, but without sandbags. When I reached the point where I had started, a far-too-enthusiastic volunteer told me I could ditch the bag and “Really go for it!” It sounded like a good idea, but my legs, my lungs, and, increasingly, my mind would not comply. So I took up a strategy I had come to employ the last few years: I would chip away. I would run as best as I could from one barrel to the next, then walk to the next one. It was agonizing, and agonizingly slow, as I was at first lapped by the race leaders and then passed by people who, in my alternate reality, had no right passing me. Women with cellulite in bike shorts. A man, much older than I, who smiled at me and said, “Not bad for an old guy, huh?”

When I finished, finally, mercifully, that mile in the sand, I doubled over at the knees and watched my dripping sweat form miniature concretions on the sand underneath me. Luke, my twelve-year-old son, approached cautiously. I had seen him watching over the top of a book while I struggled by with the sandbag.

“Hi,” he said.

“Hi,” I gasped. “What did you think of that?”

“I thought this was a race.”

“It is.”

“You didn’t look like you were racing. You didn’t look like you were trying very hard. Some of those other guys were putting out”—a phrase we often used to mean working hard—“and you weren’t.”

Here I was, my legs jelled and my lungs and breakfast both about to come out of my throat, and my own seed was telling me I wasn’t working hard enough.

The truth is, I didn’t need him to tell me that. I have been telling myself that nearly every day of my life, and especially since I first started the particular form of training called CrossFit. Those who follow CrossFit, by doing the Workouts of the Day (WODing), are known for the fervor they feel for the program, and the true belief they place in its tenets. The results are undeniable. Those who strictly follow the exercise program and its attendant dietary regimens like the Zone or Paleo diets, develop amazing physiques marked by the broad chests and backs, skinny waists, and huge quads of the actors who performed in the film 300, all of whom were whipped into shape by trainers with a background in CrossFit. The idea is to create athletes who can do lots of different movements quickly, and for a long time. In other words, to be prepared for anything the physical world might throw at you.

All you have to do is lift more weight than you thought you could more times than you thought human in as short a period of time as possible. Or perform gymnastics moves, plyometrics, and calisthenics in agonizing combinations designed to identify and rub out your weaknesses. Or impale yourself on a rowing machine or on runs ranging anywhere from ten yards to ten kilometers. Most CrossFit workouts last less than twenty minutes and involve some combination of the above. The trick, however, is going as fast as you possibly can. To complete As Many Rounds as Possible (AMRAP) in a prescribed period of time, or to do a set number of repetitions as quickly as possible. Yes, CrossFit hurts. It’s supposed to hurt. If it didn’t, the thinking goes, then everybody would do it. The fact that it seemed like everybody was doing it didn’t dawn on me for a while: there are more than ten thousand CrossFit gyms around the world, and more than two million people count themselves among the faithful.

I first learned about CrossFit in, of all places, a 2005 article in the Thursday Style section of the New York Times. I, like a lot of people who count that piece as their point of entry, was intrigued by the description of a sport with its own mascots: Pukie the Clown, who often visited athletes, and Uncle Rhabdo, short for rhabdomyolosis, a dangerous condition caused by muscle breakdown from intense exercise. Not that I wanted to puke or end up on dialysis, but I did want to learn more.

At the time, I was the editor in chief of Bicycling magazine, and in excellent cycling shape. The article intrigued me, however, because it was published at a point in the year when I was looking for something to do in the winter as an adjunct to my indoor cycling training. I spent some time on crossfit.com, which was rich with illustrative video files that demonstrated the exercises. And then, in a gym, I tried a workout. It was utterly impossible for me to finish. Here I was, capable of riding a bike 100 miles over the French Alps, but incapable of lifting 100 pounds over my head, or doing 25 push-ups, or completing three 800-meter runs.

So I tried it again. And again. And again. I made some headway, just enough to keep me coming back. When spring rolled around, I got back on my bike but kept doing a couple of CrossFit routines each week with some rudimentary weights and mats in my garage. My cyclist’s sunken chest started to grow, and my shoulders, rounded by endless miles hunched over handlebars, squared off. I attended a weekend-long class, a “cert,” designed to teach me the fundamentals of the program. I went, I took notes, I particip

ated with the other students, came in near to dead last in the sample workouts. But I didn’t care. I loved it, even if it left me gasping for air and prostrate at the end of each workout, and unable to climb the thirty-two steps from Penn Station to Eighth Avenue the next day.

But I wasn’t fully committed. I still ate whatever I wanted, whenever I wanted. I rode my bike and I swam, and I dabbled in CrossFit. I could now complete workouts that would leave most men my age injured or crying or both. And I could pretty much do whatever activity I wanted—swim a mile, ride seventy-five, hike all day—without hurting myself. But I couldn’t complete all the CrossFit exercises as prescribed. I couldn’t, as CrossFitters say, Rx. Muscle-ups eluded me. My pull-ups were woeful. And while I had learned the techniques of the Olympic weight moves, the amount of weight I could handle was, on a good day, equal to the women’s standard. The spare tire was stubbornly still inflated.

I was fit. But not truly CrossFit.

And I showed it that day in Avon. After the run, we lined up in front of chin-up bars to see how many “strict” pull-ups we could do. A strict pull-up is just that. You hang, arms fully extended, from the bar, with your palms facing away from you. You keep your legs and hips still, and you use all your upper body strength to get your chin over the bar. You then drop back down, all the way down, hanging, and do it again, as many times as you can. The guys ahead of me were doing 11, 17, 23.

I did three.

I fared better at the burpees, that old gym class chestnut of throwing yourself flat out on the ground, then hopping back up as quickly as you can, jumping up and clapping your hands over your head. I was able to do 32, again in deep sand, in the prescribed two minutes. Respectable. After a little rest, I squeezed out 52 sit-ups in two minutes. That was about average.

And that was that. Run in the sand. Do some calisthenics. I finished close to the bottom of all male competitors; there were a few guys in my age group slower and weaker than me. But not many. I took some solace in that fact that not many men in their forties had decided to do this.

By nightfall, I’d be unable to do much of anything but lie on the couch and wonder why, after all this training, I sucked as badly as I did. The thought was compounded by another question: Why did I want to pursue something I sucked at while making myself so goddamn sore? What was it about this stuff?

I thought back to a moment from earlier in the day, before the competition started. I had checked in, pinned my race number to my shorts, and started to warm up, moving my arms and legs in slow, ever-expanding circles to loosen the muscles, get the blood moving and slowly raise my heart rate. It was a routine I had followed for years before events like the Warrior Challenge. Before swimming across Tampa Bay or Chesapeake Bay or along the shores of St. John in the U.S. Virgin Islands. Before the Empire State Games swimming championship. Before the Boston and New York City marathons. Before climbing Mount Rainier in summer or in the White Mountains in winter. Before every rinky-dink 5K I ever ran. Before track meets, bike races, indoor rowing competitions, cross-country ski races, snowshoe races, triathlons, biathlons, duathlons, kayak races, mountain bike races. All of them, with me warming up the same way. Slow circles, slow, easy motions. Warming up, getting ready.

And wondering, before each and every one of them, just what the fuck was I doing here? What was I trying to prove, and to whom was I trying to prove it? What was I after and could it even be found in something as ultimately trivial as, say, a pull-up contest? Some people invest their self-worth in the quality of their relationships or their work, or perhaps with their relationship to higher powers. For some reason, I had decided that meaning lay in how many burpees I could do in the sand or how fast I could swim a mile.

These thoughts had been with me as long as I could remember, and I’d never been able to answer the question or banish the doubt. They didn’t prevent me from competing, and certainly not from training, which from junior high through college and then again since age twenty-six had been as much a part of my daily routine as brushing my teeth, reading the sports section, or drinking coffee. The questions often came up before workouts, too. They asked themselves loudest before races, but they nagged every day. If the unexamined life was not worth living, then I was in need of a checkout. Because I couldn’t answer questions that had haunted me so long I couldn’t remember when they first raised their hands. And I was sick to fucking death of them nagging me.

I needed to answer the questions. It was time. They had been with me long enough. I knew that deep down, this had very little to do with exercise. I was hoping to find some other, larger truth in all this. I was nearing fifty, and I was feeling weird. I had a job. I had my health. I had a family and friends and people who loved me. But I often felt like a spectator in my own life, overwhelmed by responsibilities and the sense that at any moment I would fail, that I was still not doing exactly what I wanted to be doing, because I still didn’t know what that was.

I had stumbled across a saying that soldiers and marines in Iraq and Afghanistan had been using to describe a coping mechanism that got them through their deployments: Embrace the Suck. Yeah, it sucks here. But here you are. And wishing it didn’t suck wasn’t going to make it any less sucky, so make the best of it by embracing it and seeing what lessons can be learned from it.

There was a lesson in there for my whole life. I had just left a comfortable job I had held for eleven years, and traded an understanding, supportive boss for four demanding new ones in the form of the board of directors of the Internet start-up I was running. I was telling prospective employees that the next couple of years would be uncomfortable and could, quite possibly, suck.

That was it: I wasn’t embracing the suck. Rather than leaning in to the pain of a workout or a race to hear what it was telling me, I was avoiding it and letting my mind wander so that I wasn’t getting the whole message. As a result, I wasn’t getting the whole benefit. Sure, my muscles got sore and I gasped for breath. But I had the strong sense I was missing something. My wife, Anne Thompson, is one of the most ferociously competitive people I know. She’s capable of impaling herself fully on a workout, jumping onto it without fear. She never says a workout was good, rather that it sucked, which is her way of saying that it was good. She’s far more interested in the benefit of the workout rather than the process. In that respect she is my opposite. She regularly looks at me after a workout and shakes her head. “You could have gone way harder,” she says.

That would change. Instead of saying, “Wow, man, these hundred burpees are just about the worst thing ever besides a kick in the nuts,” and thinking about how awful the next twenty minutes were going to be, I’d lean in. I’d listen to it. There was an answer in there somewhere. I’d hear that what the soreness and lactic acid was telling me, what weaknesses it was pointing out, what I needed to work on. And who knows? If it was going well, maybe I’d be able to say, “Wow! those burpees really do make every muscle in your body stronger!” When the bile rose in my throat, I’d taste it to see what message it carried (besides the importance of never, ever drinking coffee before a WOD).

The path to the answer to the question “Why the fuck am I doing this?” was clear.

I needed to embrace the suck.

1

The WOD

I have studied the ceiling of the Annex, an athletic training facility in the small industrial area of the otherwise leafy suburb of Chatham, New Jersey, as if it were the Sistine Chapel. It is a wonder of textured white, thanks to the corrugated panels that form its body, with rafters running the length of the building, and beams spanning the width. Heating ducts, the pieces numbered 1–25 (with 18 and 5 repeating for some reason), run down the length of the interior side, and wires hang in straight lines to nowhere, probably remnants of the building’s previous life as a workshop. The building is not square: the long exterior wall that forms the back slants away ever so slightly toward River Road. The runners for a sliding overhead door that opens into a loading dock hang just below the

ceiling. Four thick climbing ropes are tied to beams a third of the way in from the sliding door, and the heating system, built by Reznor, a company founded by an ancestor of Nine Inch Nails frontman Trent Reznor, hangs near a vent to the outside. Speakers dangle from two locations and pour out a never-ending stream of high-beats-per-minute music that ranges from rap to classic rock to house, depending on who’s controlling Pandora on the iPhone plugged into the sound system.

I’d never paid much attention to a ceiling, any ceiling, before I came to the Annex. But for the past couple of years, three or four mornings a week, at various times between 5:30 and 6:30 a.m., I lie on the small patch of bright green Astroturf or the hard rubber mats that make up the Annex’s floor and I stare up, toward the roof. Sometimes it’s the idle, thousand-yard stare of someone who has been awake for a mere fifteen minutes and is fighting to gain consciousness even as he tries to unlock his stiff and unresponsive muscles with the foam rollers, lacrosse balls, and rubber stretching bands laid out on the floor. But more often it is the gaping-eyed, almost-panicked stare of someone who has just finished a workout that has taxed my brain, my spirit, my lungs, my guts, and every fiber of muscle in my body and has left me sprawled on my back on the floor, arms and legs spread-eagle, my chest heaving in a desperate, redlined fight for breath as sweat pours off every inch of skin.

That’s the case this Tuesday morning. The 5:30 class, made up today as on most days of eight largely silent men ranging in ages from thirty-two to fifty-one and coached by a twenty-four-year-old former collegiate lacrosse player turned J. Crew stylist, has spent the last fifty-two minutes burning through a routine that starts with a warm-up that begins slowly with stretching and builds to a jump-roping crescendo as challenging as many workouts I’d done before I found CrossFit. (Or, as a T-shirt worn by one of my fellow travelers says, “Our Warm Up is Your Workout.”) The warm-up is followed by an Olympic weightlifting session in which we do five sets of repetitions each of a lift called a back squat, which calls for us to put a bar loaded with as much as our body weight on our upper back while we drop under it into a squat before standing up. Then, and only then, does the real workout begin. Today, we are to do as many rounds as we can in fifteen minutes of the following three exercises: jumping from a dead stand still onto a 24-inch box ten times, swinging a 42-pound ball of steel with a handle called a kettle bell between our legs and over our heads ten times, and performing ten burpees, perhaps the single worse exercise in the CrossFit repertoire, a move that calls for us to throw ourselves prone onto the ground then leap back up into the air, clapping our hands over our heads.

Embrace the Suck

Embrace the Suck